Clergy-in-training are cautioned time and again: Do not fall in love with a parishioner. It violates all the relational mores we are supposed to keep. It is not a relationship of equality. You, the clergy-person, hold forgiveness and sacrament. You are always the parent, never the partner.

I incautiously overstepped that rule once.

Lars was in hospital. Not the most modern, or the biggest, or even the closest, but the tiny twelve bed facility where I served as chaplain once a week and on call. I did not know Lars; I was new in the parish, and he rarely attended service. He was more likely to go to the Roman Catholic church on the far side of the parish boundary with his caregiver.

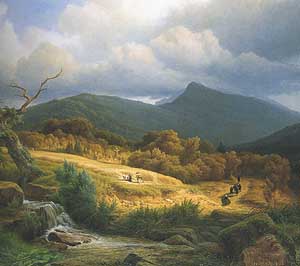

Lars was no longer young in body. His vision and hearing were failing. He had been a life-long bachelor, in a tidy little house in a glen over the ridge from the rectory and church. It was set in a lush meadow, with a merry brook running through. I doted on that farm. It evoked ancestral memories.

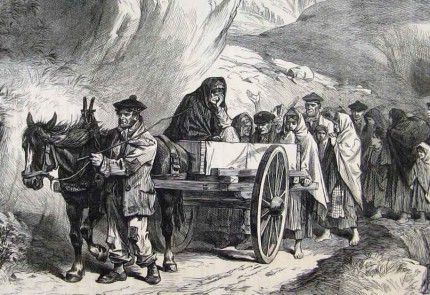

Lars was sitting up in bed, in the concentrated care room right off the nurses’ station. His caregiver, Antonia, was with him. It was late. There had been a difficulty of some sort getting him to hospital, a doctor arriving late, Lars detained, gray and coughing, in the emergency examining room for a couple of hours. It was dark: I had to get the porter to let me in.

With an oxygen cannula in his nose, Lars was improving. I whispered to Antonia as I met her, “Heart attack?” She shook her head. “No, just bad pneumonia again. It comes on him suddenly.” I held out my hand to Lars. “I don’t know you,” he said softly, in a sibilant Danish accent. “But I know who you are. Andy speaks highly of you.”

I looked to Antonia. “Andy – Anders Madsen. His nephew.” A warden, active in the church.

I pulled up a chair to the bedside. Antonia excused herself to go home.

“Not yet, Tonia,” Lars said. “You should get the reverend lady a cup of coffee or tea first.”

Antonia smiled. “If she wishes.”

I waved her out the door, protesting that I needed nothing. I was impressed, though, with the chivalry of this elegant elderly man, who addressed the hospitality owed a guest even as he was ill in hospital.

He turned clear blue eyes on me, and a high wattage smile. I returned the smile.

“My dear reverend lady,” he said. “Why are you here?”

“Because you are ill, and I have come to pray for you.”

“You don’t know me at all. You have never met me before. And yet you came all this way to see me, in the dark!”

“Of course.”

“Because it is your job?”

“Because I wanted to.”

I had received a call from the duty nurse, asking me to come in. This wasn’t unusual, as I was the chaplain on call, and the clergy of record for almost half the county. I had charge of five churches with four congregations. I had two classes of confirmation students, a total of twenty-five. My parish itself was in the hundreds of square miles. There were four hospitals within my range. Despite high demand I did want to see the sick, the housebound, the elderly and the least mobile. I preferred the company of the very young and the very old.

Lars was over eighty years old. He was handsome. He was tall, upright, thin. He had a craggy Viking face, eyes the colour of summer skies, and a sharp mind. He had farmed all his life, but like some of the older inhabitants of the Settlement, he had learned to read in English and Danish at home. He had not attained many years of schooling before he was needed in the fields; still, he had educated himself.

“Come sit on the edge of the bed,” he urged me. “I can barely hear you down there.” So I perched on the outer boundary of the hospital mattress as he held my hand and asked me where I was from, who my people were, what I did with my time. I was breaking the first rule: Never sit on the bed. I was well-known for breaking this rule. I was – and am – an unapologetic hand-holder, hugger, and motherer. I kiss cheeks and comb hair. I make soup and cups of tea. I have even gotten on the bed to take a dying friend in my arms, despite my clerical collar and title.

Lars was in hospital a week. I gave him communion and prayed with him daily. I sat on the bed and held his hand. I kissed his cheek. He loved a good story. He had little breath for talking, so he let me talk about my sheep, my travels, what I had found in the countryside as I wandered with my dog.

We fell in love.

It was a beautiful and chaste love. We would sit quietly at times, holding hands. We didn’t have to express this emotion, this autumn romance. Sometimes Antonia would come in, or Anders. But mostly we sat alone, until he was discharged. I visited him at home about twice a week, with cups of tea and sweet bread made by Antonia. She joined us more often in the kitchen, and encouraged him to fill up the time with tales of his own life.

Adoption had been common among the Danes in the early half of the twentieth century. Some families took in orphans and abandoned children, Danish or otherwise, as easily as old ladies take in stray cats. Anders had been among those children, adopted by an uncle and aunt when his own parents died in an influenza outbreak. He was raised with four other adopted siblings. He remembered his childhood as happy and blissful. His adoptive parents doted on the children. They were rural poor, eking out a subsistence living on the farm, with cows, potatoes, grain fields and a large garden to manage. Dollars were earned working for other farmers, wild-harvesting hazelnuts and blueberries to sell, and cutting cord wood. Toys were handmade. Lars remembered a wooden wagon, painted red, and a homemade teddy bear. Food had been plain and plentiful. The days were long and full of work. He regretted he had not been able to attend school after age ten, but he had gained his height and strength early, and he was needed to drive a team.

He was a natural shepherd, but it had been a couple of decades since he had kept sheep. We talked sheep endlessly. Anders took him for a drive and they stopped at my pasture so he could admire my flock of Shetlands. He leaned on his cane and surveyed the ewes and near-grown lambs. “Where’s your ram?” he asked. “I didn’t keep one,” I said. “Those two over there are wethers. I will borrow a friend’s purebred ram next month.”

“I do like the coloured fleeces,” he said, gently scratching the ears of Gala, a grey ewe with a lively white splash on her black head. “Oh, these are fine looking animals, reverend lady. You have them spoiled.”

I promised to bring a lamb or two by in the spring, to see if he wanted to keep a pair as pets. The Shetlands are small, intelligent sheep, hardy and thrifty. He would look forward to it, he said.

I felt as if an old Viking Lensgreve had visited me.

Antonia called me from the hospital a few days later. “Lars has had a relapse,” she said. “There is a lot of fluid building up.”

I went into the hospital to see him that afternoon. He was very weak, but his smile was still sweet and strong. I sat on the bed and gave him communion, supporting his head as he received the wine, and finishing the chalice myself. He had no strength for words, so I sat with him, held his hand and sang softly, old hymns I knew by heart.

After a while, he said gently, “You go home, reverend lady. I will see you again.”

I kissed his cheek. It was cold. There was a hint of a tear in his eye.

Anders called me later that night, as I sat in front of my fireplace, reading John Gardner’s novel of the Protestant Revolution in Scandinavia, Freddy’s Book. It is a tale of nobility, spirituality and defeating the devil in the far north. I had just poured a small glass of sherry.

“Lars has passed,” Anders said. “Antonia and I are here. Do you want to come in?”

Of course I did.

I said the prayers to welcome the soul to heaven, anointed the body, and kissed his very cold cheek.

The day of the funeral, a storm took all the autumn leaves from the old maples in the cemetery. The funeral was the plain Book of Common Prayer service. I walked up the aisle with Lars, not as the love of the heart I had become to him, but as his priest. It had been a pure love; and though I was sorrowful, I knew he had borne my love to heaven, and offered it at the throne of God. A chaste, noble love; the truest love.

We buried him among his family and friends, while his surviving nieces and nephews stood at graveside. I picked up a handful of damp grave soil to begin the words, “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” I stopped, looked across the grave at a young niece, and warned her, “You will put out that cigarette right now, Miss, and show your uncle some respect. You will not smoke in my cemetery.”

The cigarette was stubbed out with an annoyed sigh. In a strong voice I finished the office. A few roses were cast into the grave as the casket was lowered. The congregation hurried back to the church hall for coffee and tea. I stood at the head of the grave as the hole was filled.

“Goodbye, Lars,” I said. “I love you. I will see you again.”

My Life and the History of the World